The C.E.O.s Who Just Won’t Quit

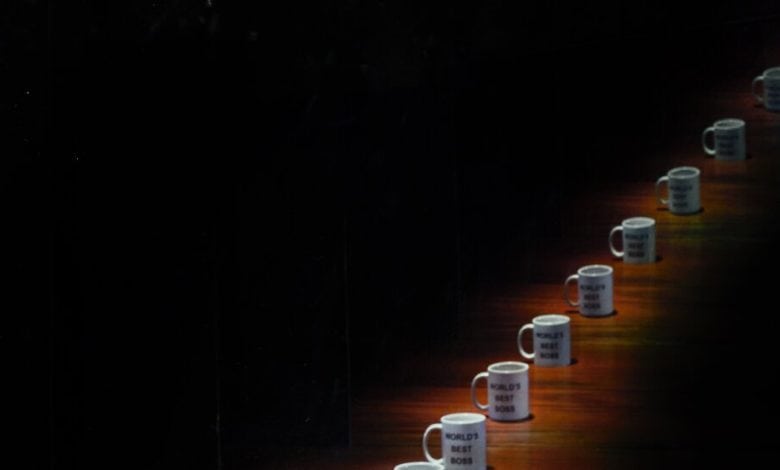

In September 2013, in a darkened auditorium, Microsoft’s chief executive, Steve Ballmer, faced a roaring crowd of his employees. “You work for the greatest company in the world,” he bellowed. “Soak it in!” Ballmer was known for his exuberance. He had been nicknamed “Monkey Boy” for the bar-mitzvah-style dance moves he deployed to motivate employees at another company meeting. He once damaged his vocal cords while giving a presentation on software.

Listen to this article, read by Sarah Mollo-Christensen

Even so, there are few scenarios in which a middle-aged corporate executive can be treated like an aging rock star by thousands of fawning employees. But on this day, Ballmer was doing something truly admirable: He was retiring. “Microsoft is like a fourth child to me,” he said as he left the company’s stage, his eyes glistening with tears, to the opening chords of “(I’ve Had) The Time of My Life.”

Ballmer’s retirement earned him the corporate equivalent of a Viking’s funeral. But most people seemed to agree that his departure, 14 years after he took over the company from his college classmate Bill Gates, should have happened years earlier. Around the time Ballmer announced his plans to go, the company’s stock price was lower than when he started the job. The media was bemoaning Microsoft’s “lost decade.” While its tech rivals had seized on new markets, Microsoft had changed fairly little. Apple dominated smartphones, Google prevailed in search and giants like Facebook — which didn’t even exist when Ballmer took the reins — stood atop a whole new sector of the economy. With the arrival of Ballmer’s successor, Satya Nadella, Microsoft’s stock price soared.

Of the many riddles that confront corporate chief executives in the course of their work, perhaps the most important is when to quit. It’s the maneuver that cements a C.E.O.’s legacy. The cost of overstaying is steep, especially when tallied in missed opportunities: Ballmer famously scoffed at the invention of the iPhone, believing that businesspeople would never want it because it didn’t have a keyboard. Reflecting on Ballmer’s leadership, the Harvard Business School executive fellow Bill George told me: “It was obvious certainly at the 10-year mark, maybe before, what he was doing was cheering on the strategies Bill Gates had put in place.”

Over the last several decades, as Americans have lived longer, career has become the ascendant source of meaning in a country increasingly eschewing religion. And now, perhaps inevitably, workers of all kinds and levels say they are going to defer retirement. That’s especially true of striving and hard-driving institutional leaders; just look to Washington D.C. But particularly for the people running corporate America, the reasons to overstay in leadership are even more compelling. There’s the authority, the personal assistant, the corner-office views, the feeling of being needed, the flattering, the deference and, of course, the money. American chief-executive pay in 2022, across the S&P 500, averaged $16.7 million. When power and pay is that densely concentrated, people will cling to it whether or not it’s good for business.