J.D. Vance’s Strange Turn to 1876

The most favorable gloss you could give to Donald Trump’s effort to “Stop the Steal” is that it was an attempt to deal with real discrepancies in the 2020 presidential race as well as to satisfy those voters angry about the conduct of the election.

This, in fact, was the argument made by Senator J.D. Vance of Ohio in a recent interview with my colleague Ross Douthat. Vance defended the conduct of the former president and his allies, and condemned the political class for its attempt to “try to take this very legitimate grievance over our most fundamental democratic act as a people, and completely suppress concerns about it.”

Vance briefly analogized Trump’s attempt to contest the election to that of the disputed election of 1876, describing the latter as an example of what should have been done in 2020. “Here’s what this would’ve looked like if you really wanted to do this. You would’ve actually tried to go to the states that had problems; you would try to marshal alternative slates of electors, like they did in the election of 1876. And then you have to actually prosecute that case; you have to make an argument to the American people.”

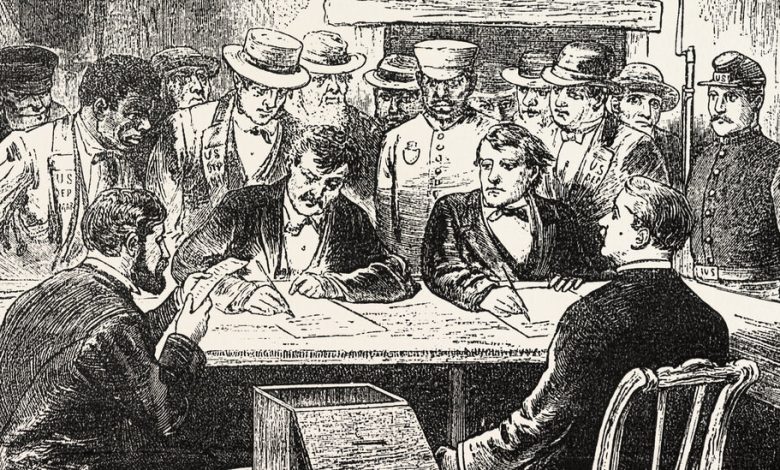

Let’s look at what happened in 1876. In that race, the Democrat, Gov. Samuel Tilden of New York, won a majority of the national popular vote but fell one vote short of a majority in the Electoral College. The Republican, Rutherford Hayes, was well behind in both. The trouble was 20 electoral votes in four states: Florida, Louisiana, Oregon and South Carolina. In the three Southern states, where the elections were marred by fraud, violence and anti-Black intimidation, officials from both parties certified rival slates of electors.

Hayes believed, probably correctly, that had there been “a fair election in the South, our electoral vote would reach two hundred and that we should have a large popular majority.” As the historian Michael Fitzgibbon Holt noted in “By One Vote: The Disputed Presidential Election of 1876,” “Had blacks been allowed to vote freely, Hayes easily would have carried all three states in dispute, Mississippi, and perhaps Alabama as well.”

In the weeks following the election, Democrats and Republicans in those states would fight fierce legal battles on behalf of their respective candidates. In South Carolina, where an election for governor was in dispute as well, Democrats threatened to seize the statehouse by force. The predominantly Black Republican majority in the state legislature tried to certify the Republican candidate as the winner, and Democrats went as far as convening a separate legislature, where they crowned their candidate, Wade Hampton III, the victor.