Life, Death and Life After Death in June’s Graphic Novels

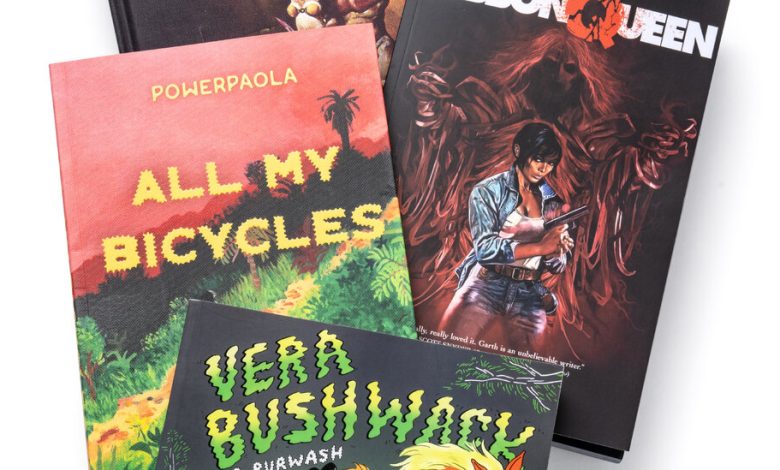

Though it is customarily served cold, revenge is a surprisingly versatile dish. Take, for example, Garth Ennis and Jacen Burrows’s THE RIBBON QUEEN (194 pp., AWA Studios, $19.99), a grisly crime/horror hybrid with a lot on its mind. Our heroine, Amy Sun, is a detective for the New York Police Department and a reluctant investigator into the suspicious suicide of a young woman who had recently been rescued by the chauvinist leader of a decorated tactical unit.

It’s a setup one might expect from a Tana French novel, but Ennis and Burrows, who love to test their readers’ tolerances for viscera, are headed into far wilder territory. The pair has worked together often, sometimes on Marvel’s “Punisher” comics and sometimes on their own eye-wateringly gory zombie series, “Crossed,” but here they are concerned with subjects that fit comfortably in neither venue: the problem of misogyny, and the danger of police corruption in the aftermath of the widespread anti-brutality protests in 2020. Into this volatile mix, Ennis and Burrows thrust Bella Rhinebeck, a murder victim, and her posthumous patron, a monstrous being that can’t be easily described, not even after seeing it in action in the book. The dialogue throughout “The Ribbon Queen” is sharp and contemporary, and Burrows’s renderings are carefully detailed and realistic. The book’s jolting supernatural scares are that much more frightening for the contrast.

What does it mean to live independently, or even to live well? Those are the questions that animate Sig Burwash’s VERA BUSHWACK (236 pp., D&Q, $29.95), a remarkable new graphic novel about a young logger named Drew who lives a rich fantasy life as a chain saw-wielding cowpoke while dealing with the logistical demands unique to a woman who wants to live by herself, in the woods, with her dog, Pony, and no one else. (Vera is the name on the side of Drew’s motorcycle, which transforms into an orange horse in her daydreams.)

Burwash, who uses they/she pronouns, gives the book’s art a lovely personality. It is surprisingly plastic; sometimes their renderings of Drew and her environs are simple contours, sometimes the images are drawn from such a height that they’re almost maps of the forest where Drew lives, and sometimes a few pages will look deliberately cartoony.