A Proud Texan Reckons With Her State’s Complicated Past

WE WERE ILLEGAL: Uncovering a Texas Family’s Mythmaking and Migration, by Jessica Goudeau

I never knew my father’s father, a Texas preacher who died when my father was 2 years old. As a bookish kid growing up in San Antonio, a city swirling with Texas history and myth, I often thumbed through the pages of my grandfather’s sermons and personal library, which lined the walls of my childhood home. What, I wondered, could those books tell me about him, my history, and myself?

Unbeknown to me, during those same years, Jessica Goudeau was also growing up as a bookish kid in Texas with deep roots in the same denomination, poring over old family histories and imagining herself into the sagas about white Texans that they frequently related. In her new book, “We Were Illegal,” a stirring mixture of memoir, genealogy, history and hopeful manifesto, Goudeau turns a searching, critical eye back on her family tree and its many Texas branches. Among them was a great-grandfather who helped found her alma mater, the same Abilene college where my grandfather, the preacher, got his degree. As big as Texas is, it can be a small world.

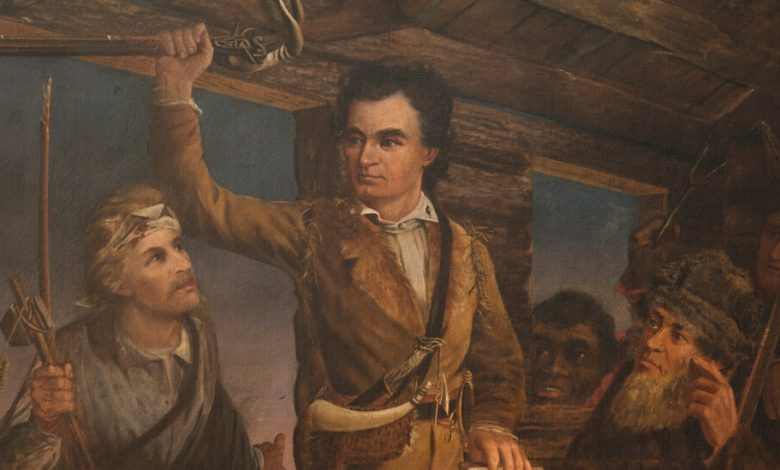

Goudeau’s book unfolds as a series of discoveries about relatives who all happened to settle in Texas at key moments in its creation as a state and as a story: an emissary to Mexico for a colony of Anglo settlers in the 1820s; a soldier in the Texas Revolution who died at Goliad in 1836; a key combatant in a series of bloody political killings later remembered euphemistically as a post-Reconstruction family “feud”; and a Texas Ranger whose dark secrets were long obscured by the heroic representations of white lawmen in American popular culture.

Informed by recent scholarship on the history of slavery, racism, anti-Mexican border violence and Native dispossession in Texas, the book’s chapters are courageous profiles more than profiles in courage. Goudeau is unsparing in her determination to tell “hard truths” about the past that school curriculums and family genealogies did not always teach her as a child or young adult. She learns the names of people enslaved by her ancestors. She relates the history of white settlers’ genocidal violence against the Gulf Coast Karankawa people (who she was taught had simply “disappeared”). And she confronts family stories of sexual abuse and complicity in murder. Throughout, but especially in the first and last sections, she spotlights the experiences of women in her family, whose difficult lives have typically been elided by mythic stories about Texas frontiersmen.

The result is a compelling but wide-ranging narrative that sometimes struggles to stay in focus. The author of a previous award-winning book about refugee resettlement in contemporary Texas, Goudeau argues that reckoning with family and state history can serve as an antidote to poisonous politics and polarization today. As she studied works of history to contextualize her relatives’ stories, she “started reading them almost like societal self-help books,” and at times that seems the intended genre for this book, too. She sees earlier episodes of violence in Texas as precedents for the same current of “extremism” on display in the present, a recurring motif whose broad strokes sometimes blur the detailed brush work in her portraits of individual people, places and moments.