Why We’re Living in an Age of Twins

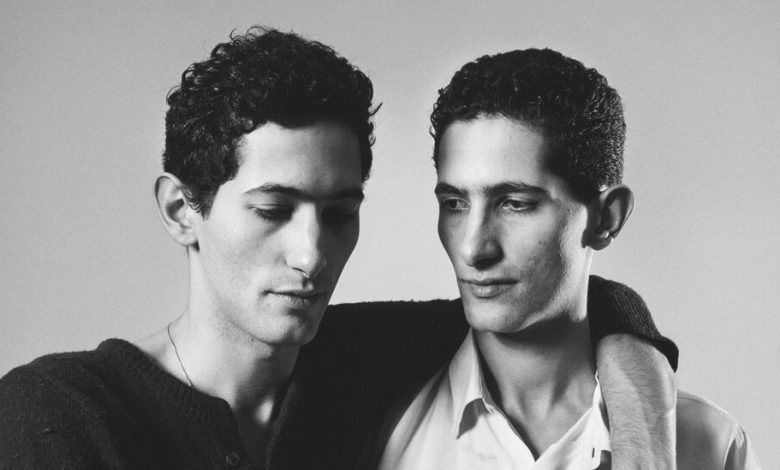

THE GREAT LOVE (or should I say, loves) of my preadolescent years in India was a pair of identical Danish twins. Charlotte and Christina were the most exotic things the British School in New Delhi had ever seen. They appeared like two beams of Nordic sunshine during those final days of India’s Socialist isolation in 1990 — blond, elfin, androgynous and (it has to be said) tantalizingly interchangeable. Charlotte was the extroverted one, impish, funny; Christina was quieter, a touch glacial. I was a Charlotte man, but went out briefly with Christina, which may have only meant a few slow dances to Guns N’ Roses’ 1991 hit “November Rain.” I was aware even then, at that age when so much is felt and so little articulated, of there being something compelling in giving my tween heart to one twin while going out with her double. Identical twins have it rough. As soon as we see them, fetishizing their likenesses and dissimilarities, we turn them into proxies for ideas. We revel in our ability to tell them apart, as if it were up to us to impart individuality unto them. We marvel at the sureness of our eye, treating them like human trompe l’oeils. We hardly stop to consider the actual reality of identical twins before extracting metaphorical power from them. There lies a chasm between biological fact and the captivating game of mirroring and doubling that we, as humans, love to play, where likeness has the inverse effect of drawing attention to deeper differences.

Listen to This Article

Open this article in the New York Times Audio app on iOS.

Identical twins are our supreme analogy for the replication and splitting that, on a cellular level, spurs our growth as a species; as such, they are in some basic way our earliest introduction to the power of dualities. “Within the mind,” writes the Italian author Roberto Calasso in “Ka” (1998), his imaginative retelling of Hindu myth, “came that split that precedes all others, that implies all others. There was consciousness and there was an eye watching consciousness. In the same mind were two beings.” We grow up to discover there are names in every culture for that — yin and yang, the Apollonian and Dionysian, Vishnu and Shiva, thesis and antithesis, the law of contraries, the dialectic.

Twins have appeared in culture after culture, in era after era, in religion, mythology and art, here as objects of veneration and divinity, there as something fearful, repugnant and disturbing, even worthy of being put to death. Every time they come among us — now in the toothpaste green dresses of the little girls in Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining” (1980), bidding us to come play with them; now as the proud Ashvins of Hindu mythology, surgeons to the gods, riding across the sky with their father, the sun — their presence has been imbued with meaning. They’ve been symbols of light and shade, divinity and mortality, good and evil; embodiments of enduring love, like the Greek Dioscuri, Castor and Pollux, as well as mortal enmity, such as the Bible’s Jacob and Esau. They’ve given us Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s figure of the double, which, in his 1846 novel of that name, allows him to pry apart man and consciousness; they’ve served as Freudian expressions of unheimlich, or “the uncanny.”

A few years ago at Tate Britain in London, I remember standing mesmerized in front of an early 17th-century painting — “The Cholmondeley Ladies” — of two seemingly identical women, sitting upright in bed in full Jacobean dress, holding two babies in burnt red robes. They were “born the same day, married the same day and brought to bed [gave birth] the same day,” the inscription read, even as this emphasis on sameness drew me to their differences. “The anonymous artist seems to have intuitively understood,” writes the art historian James Meyer, referring to the painting in his 2022 essay “The Double: Identity and Difference in Art Since 1900,” “some four and a half centuries before Seydou Keïta and Diane Arbus trained their cameras on twins in matching dress that a resemblance so extreme incites a perception of unlikeness, of difference, discernible in the subtle variations in the young women’s expressions, the shapes of their noses and eyelids, the divergent hues of their eyes.”

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Want all of The Times? Subscribe.