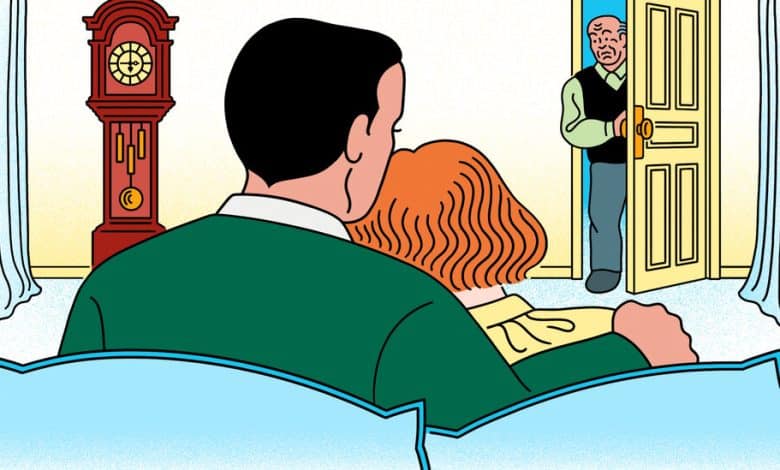

My Wife Plans to End Her Life. Should I Tell My Very Religious Father?

In a few weeks, my wife will have an accompanied suicide. Her daily pain and increasing loss of function led her to this difficult decision, after more than 25 years of battling multiple sclerosis. We’ve recently started telling friends and family about what’s coming, which has been an incredibly hard and yet beautiful process.

But then there’s my father. He’s very religious, and I’m certain he’s strongly opposed to assisted suicide. He is also convinced that all medical problems can be solved if you just ignore doctors, do your own research and follow your instincts. Once he hears of my wife’s decision, I know he’ll be very upset and go into overdrive, trying to find a solution. The end result will be extra stress for my wife.

On the other hand, if I wait to tell him after the fact, it seems likely to leave a deep, painful emotional scar that he wasn’t consulted and that he didn’t get to say a proper goodbye. This feels like a no-win situation. Is there any other option? — Name Withheld

From the Ethicist:

Because what you’re describing has met vigorous secular as well as religious resistance, it’s worth stressing that the decision your wife has taken is one she was morally entitled to. Assisted suicide occurs when people of sound mind end their own lives with drugs prescribed by a doctor. (With euthanasia, someone else administers the drugs.) Some groups condemn assisted suicide because they believe it derogates or devalues the existence of everyone living with pain or incapacity. They see it as an affront against their identity. But allowing people to make their own deeply personal decisions about whether they want to die is more naturally seen as a way of respecting their autonomy. Legal permission to end your life painlessly does not imply that anyone in particular ought to do so. Nor does someone’s choice of assisted suicide — or, in the phrase some prefer, assisted dying — entail that others in similar circumstances cannot go on living worthwhile lives.

Opponents also worry that the option of assisted suicide risks putting pressure on people to end their lives — pressure from their families or from clinicians or caretakers like the staff of nursing homes. (Anti-abortion activists make similar arguments about choice and pressure and, indeed, about the devaluing of lives.) For many patients, medical care, including end-of-life care, is currently inadequate, as opponents emphasize. Yet we don’t make a practice of denying rights because there’s a possibility that they will be abused, or because they will not be exercised in ideal circumstances.

We can certainly ask that a doctor involved in assisted suicide assess a candidate’s state of mind, making sure that the decision was reached reflectively, without coercion or wrongful influence and with an understanding of how their death will take place. But where those conditions have been met, the law should not stop sufferers from pursuing this course of action, or punish those who provide the necessary assistance. Ten states and the District of Columbia have given this understanding statutory force.