Following Yoko Ono’s Anarchic Instructions

In December 1971, a man at the exit of the Museum of Modern Art had a question for departing visitors: “What did you think of the Yoko Ono exhibition?”

Some were confused (“What exhibition?”), others irritated (“I couldn’t find it!”) or delighted (“Well I just thought it was amazing”). To a man who had trouble locating the show, the interviewer conceded, “It’s here, it’s just mostly in people’s minds.”

The man nodded. “Yes,” he said, “I thought that might be the case.”

These were some of the reactions to Ono’s “Museum of Modern (F)art,” a self-appointed MoMA debut, staged without the museum’s permission. She published a catalog, placed ads in The Village Voice and inserted a sign at the museum entrance stating that hundreds of perfume-soaked flies had been released inside. It was up to visitors to find them, the notice said, perhaps by following the errant wafts of fragrance drifting past the Pollocks, Picassos or Van Goghs.

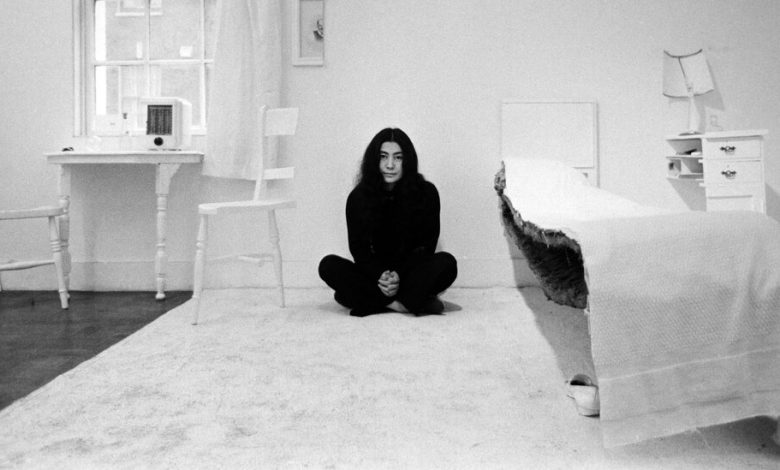

More than 50 years later, the Tokyo-born artist known for her marriage to John Lennon as much as her avant-garde (and often very funny) art has a much-anticipated retrospective at Tate Modern in London, running through Sept. 1. The show, “Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind,” contains more than 200 works spanning seven decades. Like “Museum of Modern (F)art,” which is part of the retrospective, most of those works are in people’s minds.

The exhibition takes us through Ono’s work and life chronologically. The first space immediately establishes the sense of spare elegance that dominates the artist’s oeuvre, which unfolds across performance, installation, film, text, sound and sculpture.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Want all of The Times? Subscribe.