How Not to Think Like a Fascist

ON GIVING UP, by Adam Phillips

One of the most arresting things about Adam Phillips’s work is how it resists easy summary, dissolving into a trace memory the moment you try to describe it. Over several decades, in more than 20 books — many of them slim volumes further subdivided into even slimmer essays — Phillips, a British psychoanalyst, sidles up to his subjects, preferring the gentle mode of suggestion to the blunt force of argument. His writing has a way of sneaking up on you, like a subterranean force. An interviewer once described trying to edit his comments as “sculpting with lava.”

Even Phillips’s titles tell us only so much. “Attention Seeking” (2019) sounds as if it’s about something shameful, when in fact, he says, “attention-seeking is one of the best things we do.” In “On Wanting to Change” (2021), he writes about change as an object of both desire and dread; we long for the conclusiveness of a conversion experience, “a change that will finally put a stop to the need for change.”

Phillips, who was formerly a child psychotherapist, likes to play with terms that are capacious, elastic and stubbornly ambiguous. The title of his new book, “On Giving Up,” covers the vast territory between hope and despair. We can give up smoking, sugar or a bad habit; but we can also give up on ourselves. “We give things up when we believe we can change; we give up when we believe we can’t.”

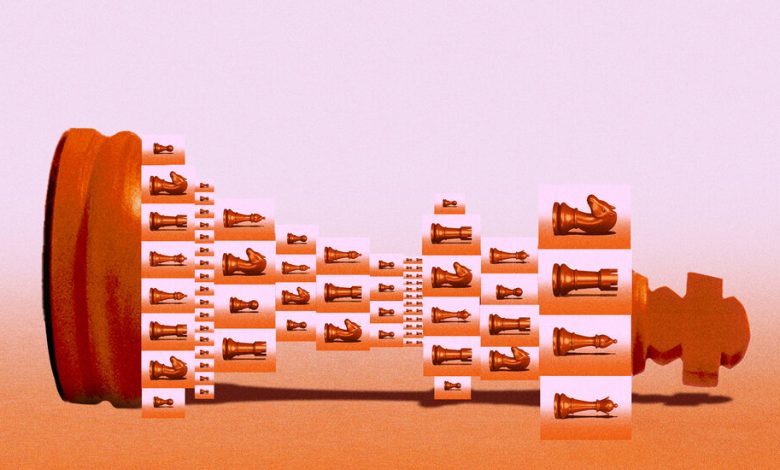

It’s this extreme and despairing definition of “giving up” that we tend to fixate on, to the neglect of what Phillips calls “the other, minor forms of giving up.” When we do think of giving up in this “minor” sense of cessation or withdrawal, it’s something that needs to be justified, because we valorize completion and commitment. But such relentless determination can also be tyrannical. The tragic hero, Phillips says, is someone who is “either unable or unwilling to give up.” Macbeth cannot pause his murderous ambition. He stops sleeping, because “sleep that knits up the ravelled sleeve of care” — or what Phillips calls “restorative giving up” — risks opening the sleeper to other possibilities. And a sense of other possibilities is corrosive to a single-minded determination.

Phillips cites work by Shakespeare, Kafka and Camus. He cites Freud, too — not as an infallible authority but as the incisive interpreter of human ambivalence who nevertheless succumbed to the lure of becoming a “dogmatic essentialist.” Feeling betrayed by the occult ideas of Carl Jung, his onetime disciple, Freud reacted protectively, by hunkering down: “Freud had to declare himself the owner of psychoanalysis and begin a whole disreputable tradition of people who need to tell us what psychoanalysis is, people who claim to know precisely what should be called psychoanalysis, as opposed to going on working out what it might be and what we might want it to be.”