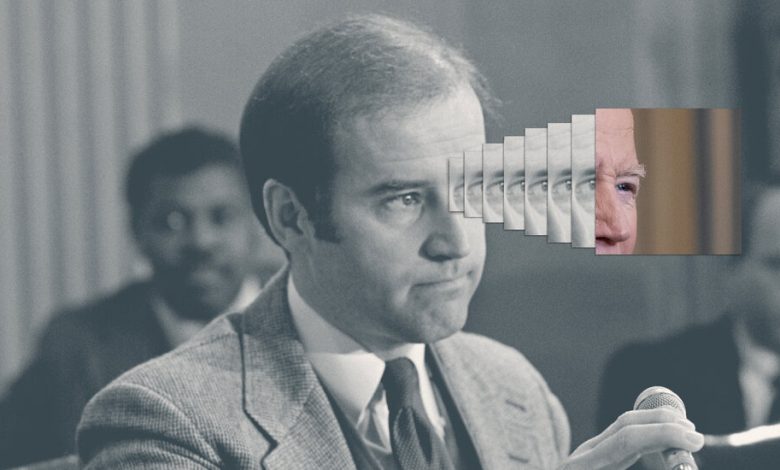

Joe Biden: The Eras Tour

Joe Biden, you might have heard, is old. I’m sure you have thoughts about that: about his mental agility and physical stamina, about his chances for surviving a second term that is scheduled to end two months after his 86th birthday. But presidential age isn’t only a medical or actuarial matter. It has a symbolic weight, a range of cultural meanings that have so far been overlooked.

Biden is 81. Donald Trump is 77. Biden’s age has become an issue in a way that Trump’s has not, because we are being asked, as citizen-critics, to judge the president’s late style. This is what we saw at the State of the Union on Thursday night.

In criticism, to speak of a late style is to highlight the way certain artists, at the end of their careers, enter a new and distinctive phase of creativity. Sometimes they produce a succession of masterpieces that both fulfill and transcend the promise of the earlier work: Richard Wagner’s final run of operas; the three major novels Henry James published at the start of the 20th century; the movies Martin Scorsese is making now. In other cases, an older artist will revisit familiar themes with a new sense of playfulness and freedom, like Henri Matisse making cutouts, Shakespeare bending the rules of genre in “The Winter’s Tale” and “The Tempest” or Bob Dylan reshuffling the pages of his own songbook.

And then there are those artists who swerve in a more radical, dissonant direction. “The maturity of the late works,” the German theorist Theodor Adorno wrote of Ludwig van Beethoven, “does not resemble the kind one finds in fruit. They are, for the most part, not round, but furrowed, even ravaged.” Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis and last string quartets often unsettle listeners with their dissonances and their unexpected harmonies.

The literary critic Edward W. Said, who wrote the book “On Late Style,” suggested that late work like this “has the power to render disenchantment and pleasure without resolving the contradiction between them.” Clint Eastwood’s recent films (notably “The 15:17 to Paris,” “The Mule” and “Cry Macho”), at once the corniest and the most avant-garde movies in his canon, fit this description. So do Philip Roth’s bitter, incandescent final books (“Exit Ghost,” “Indignation” and “Nemesis,”), which distill the prodigious inventiveness of his great middle-period novels into austere, jagged, sometimes bluntly funny meditations on sex, death and disgrace.

What does any of this have to do with Joe Biden? Politics is not art. But it is a craft, a vocation, and not many people have practiced it as long or as devotedly as Biden. In a profile this month in The New Yorker, Evan Osnos notes that “for decades, there was a lightness about Joe Biden — a springy, mischievous energy” that is no longer in evidence. “For better and worse,” Osnos writes, “he is a more solemn figure now.”