When the Rubin Museum Was Divine

A brick-and-mortar presence can be, often is, a crucial part of an art museum’s allure. The Guggenheim’s mother ship interior is such a thrill that it prepares you to love whatever’s on view. The interiors of the Frick and the Morgan are intimate enough to make you feel proprietarily, and fabulously, at home.

The Rubin Museum of Art also has design and art going for it. Housed in what was once the women’s wear wing of Barneys New York, it retains the store’s six-story steel-and-marble spiral staircase, and turns spaces conceived for leisurely shopping into ideally scaled galleries.

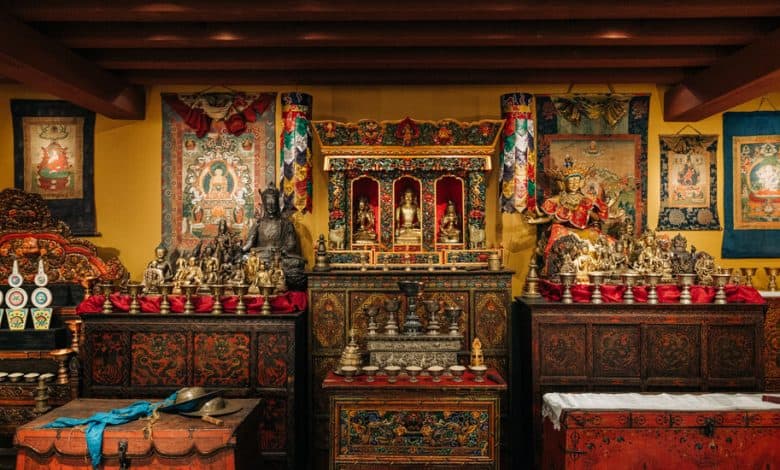

And the kind of art gathered in those galleries is, in its concentration, like nothing else in town. Mostly ancient, mostly religious, it’s all from Himalayan Asia, a region that stretches from India to China, and has, on the Rubin’s map, Tibet at its center.

With its suave look, dynamic art assembled over decades by the philanthropists Donald and Shelley Rubin, and customer amenities — a gift shop stocking artisanal goodies, an East-West fusion cafe — the museum was a hit from the day it opened in 2004, and one with a comeback vibe. It was the place you ended up lingering in just because it felt good to be there, in an atmosphere that felt calm but charged, that discouraged hurry, encouraged quiet.

In a few months all that will be gone. The museum recently announced that it would permanently leave its physical space on Oct. 6, having sold the building, with no plans to buy another. It will travel the house collection here and there, maintain a digital presence with the goal of promoting Himalayan culture internationally. It will transition to being, in its own vague words, a “museum without walls.” But from the perspective of a once-frequent visitor to its Chelsea home, I suspect it will become mostly a memory.