When Your Mom Is Famous for Hating Motherhood

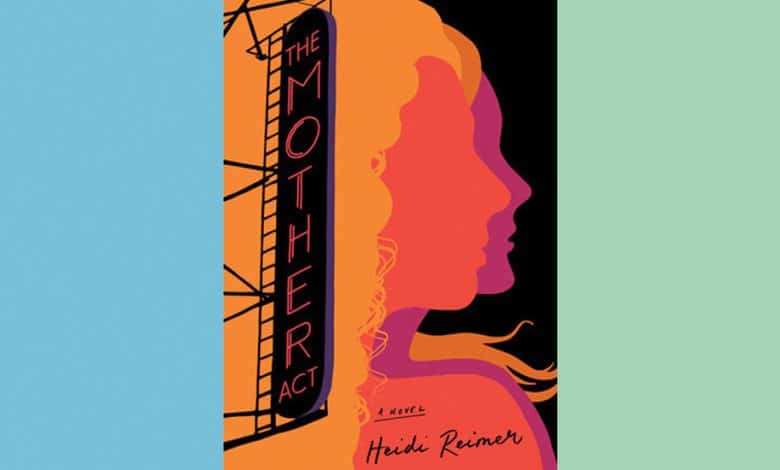

THE MOTHER ACT, by Heidi Reimer

Writing about one’s own children has always been a delicate matter. It’s itchy and complicated, and there is no right way to do it. As a child who was often a subject of the writing of my mother, Erica Jong (and sometimes my grandfather Howard Fast), I have very mixed feelings about the phenomenon. I like to think I truly hated being written about, but who can remember? Later, I found it gave me a profound lack of shame and no expectation of privacy, which helped me pursue a public-facing career I might otherwise not have. All of this is to say that as I read “The Mother Act,” I felt uncomfortably close to the topic.

One of the novel’s central characters, Sadie, is an actress and an author. Sadie’s greatest success came from writing and performing “The Mother Act,” a one-woman play confronting her decidedly mixed feelings about motherhood. (“There are moments, no, whole days and weeks, when I hate my child. I hate my child and what she has done to my relationship, my life, me.”) Sadie’s only offspring, Jude, is understandably more than a bit miffed about her mother abandoning her and then mining their relationship for material. Her father, an accomplished if considerably less renowned actor named Damian, becomes her primary parent. Mother and daughter see each other rarely; when they do, Jude is furious and Sadie is mostly oblivious or guilty.

After a childhood of performing in Damian’s traveling theater troupe, Jude grows up into an anxious, prickly young adult. (This I relate to all too much.) She attempts to make it in the straight non-actor world but keeps getting sucked back into theater. Once Sadie is more consistently in touch again, she keeps trying to reshape her daughter’s life into a pattern of abandonments and betrayals like her own.

The novel’s structure, fittingly, is portioned out in six acts like a play, alternating between both women’s perspectives over several decades. That approach can be a bit jarring at first, galloping through time and shifting perspectives in every chapter. But its complexity sneaked up on me, as the portraits of these two women start to deepen and ramify. The diverse settings and sociological locations — a fundamentalist Christian community, impoverished New York bohemia, maternity suites and summer beach towns — build up sedimentary layers. And I found myself not only sympathizing with these sometimes self-pitying and self-absorbed characters, but also revising my understanding of the earlier chapters.