Who’s Afraid of Reissued Books?

It is a truth universally acknowledged that literary critics are the most annoying people in the world. They’re elitist, or undignified. They’re divisive. They’re snobs. Their profession is, in fact, dead, and has been for decades. And upon realizing that they are irrelevant, they take themselves way too seriously.

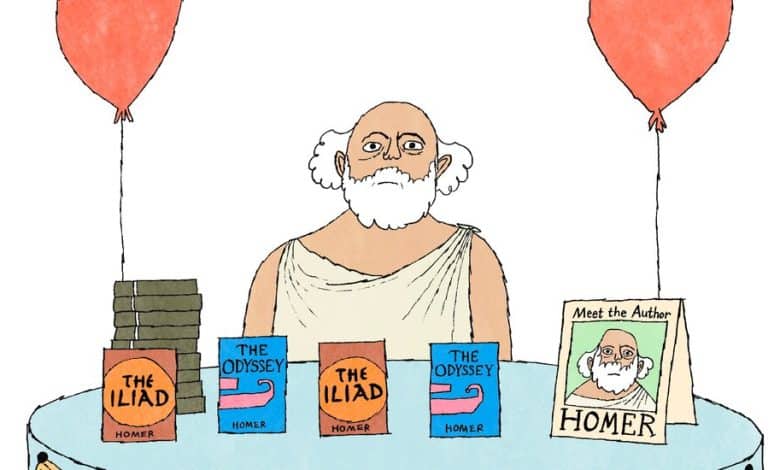

Overseeing the development of a literary culture, which is part of a critic’s job, is a process of fits and starts. Critics play a role in determining which books published today should be branded “instant classics,” which authors are best described as “little-known” and which books published in past decades or centuries merit re-examination. Beginning in the early 20th century, reissues complicated those categories. Older books like “The Dud Avocado” and “Stoner” — and even “Moby-Dick” and “The Great Gatsby” — became more famous upon reprinting than they had been when originally published.

The canon itself is in a constant, ongoing process of being shaped by book lovers who are often in disagreement not only about what qualifies as literature but also about the purpose of reading literature. But this is a feature, not a bug: The journey of discovering literature — for critics and also for everyday readers — is made of detours. A reissue, more often than not published after the author is deceased, rebalances the purpose of literature away from writer intent and more toward reader intent. Reissues are about readers recovering what is worthy about another world. As one early 2000s reissue of a perhaps forgotten 1953 classic had it, “the past is a foreign country.”

Early last year, the small magazine n+1 reiterated a longstanding policy: No dead people. Reading work from dead authors may be inevitable, but as literary critics tasked with creating and shaping the conversation, writing about dead people was considered unacceptable — because it was unfair to expect that contemporary writers, already struggling to secure attention for their work, compete with their predecessors. We need, n+1 argued, to “redirect the public’s attention to the under-read work of the living.”

The magazine has amended this policy over the years, but it was not alone in the general idea that many dead authors are often overhyped. Every so often a new list of overrated classics presents itself, identifying authors who have had “more than enough time in the sun,” crowdsourcing titles that deserve to be demoted, giving readers “permission” to not read them. This, too, is how the canon is made and remade.

Such is also the case with underrated classics. “Enough with the ‘forgotten’ writers,” a writer in The Week implored in 2017: It’s a tired excuse to talk about an author or subject we like, and it shouldn’t be necessary. Sometimes the critic rebels against the publisher and its publicist. Last summer, a review of Susan Taubes’s novel “Lament for Julia” criticized the way editors decide (seemingly capriciously) which authors deserve to be republished: by humoring the critic’s tendency to pontificate on an arbitrary subject with “indirect self-presentation,” to “hoist his reputation by raising another’s.”